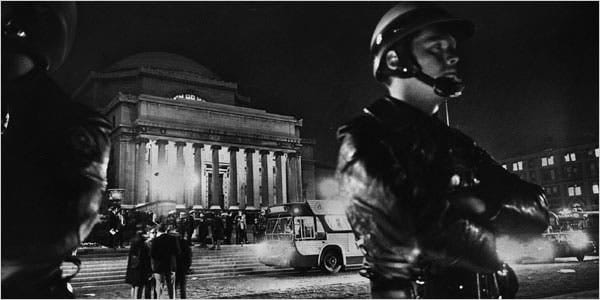

That HBO show

At this point, HBO should probably be cutting us all a check. I’m posting about your show, Sam. Me and my friends are creating public discourse about it and everything.

The smartest thing The Idol did was target the exact cultural themes necessary to generate the type of brain cell-disintegrating conversations guaranteed to make me specifically lose my mind. My favorite early hit was this chin-scratcher from Vanity Fair’s Selome Hailu, who managed to coerce a prominent LA intimacy coordinator into giving a quote that makes her sound like she’s genuinely unfamiliar with the genre of satirical fiction.

There’s a good bit in the pilot where Jocelyn’s (Lily-Rose Depp) managers forcibly sequester a male-feminist intimacy coordinator after he floats the possibility of litigation over the pop diva’s heat-of-the-moment decision to show her nipples during a photoshoot. Nipples were not included in the contract, you see.

Intimacy coordination influencer Marci Liroff — queen of having 50k Twitter followers, currently “in deep withdrawal over the end of Season 2 of #TheBear” — says to Vanity Fair:

“To be honest, I had a very visceral reaction. I was appalled … I’m not alone in this, in terms of my intimacy coordinator communities: We look at HBO as our stalwart home, so to speak … So I felt really betrayed that they were making fun of us and the job. They were using us as the butt of the joke.”

She’s speaking on behalf of the intimacy coordinator community, and it’s our duty to sit our white asses down and listen. This quote was promptly tweeted without context by Pop Crave. Nice work, girls.

To her credit, and to Hailu’s, but against Pop Crave’s, Liroff does get the opportunity to muse about an “arguable” alternative interpretation of the scene’s narrative intent later in the article:

But Liroff says she now finds herself torn: “I have been in some situations where there’s a lot of pushback from a director or producer who doesn’t quite understand what we bring to a set … So I sat with it and I realized that this actually was a very accurate — although heightened and extreme — depiction of some of the crazy pushback that I’ve experienced.”

Very cool critical thinking, Marci.

The legal formalization of intimacy coordinator positions is probably a long-overdue positive development for the safety and dignity of all screen performers, especially young actresses, although I would have no idea because I have never and will never act in an HBO production. Personally.

In general, most people seem to want to talk about the sex and sexuality in the show (duh). In turn, entertainment news media editors want to talk about the accompanying moralistic backlash from an omnipresent mob of anti-sex young adults who spend too much time online (obviously). The creepier of the millennial journalists engaged in this melodrama have been unironically theorizing a social contagion of puriteenism (throwing up in my mouth).

The evidence cited by these neo-pundits is almost always exclusively tweets or tiktoks, which are then thoughtfully embedded in their articles to maximize SEO aptitude. Okay. What if we hear them out though. Let’s watch a 27 minute YouTube video, titled “the idol is the worst show of the year 😀,” by successful young adult film and fashion podcaster Mina Le, which was recommended to me by the platform’s algorithm.

Le liked the first episode, but says that, overall, “the show is kind of boring.” I agree. She points out that the story is riddled with plot-holes. This is true. She criticizes the bland, one-note writing behind Depp’s character. Right. Broadly, she thinks most of the acting, particularly The Weeknd’s performance, is bad. Objectively correct.

Sometimes, she strays into the type of symbol-obsessed interpretive analysis popularized by internet fandoms and like, QAnon. Regarding The Weeknd’s actor-producer role in the series, she hypothesizes:

Because people have no idea who he actually is, I feel like the end result is when people watch this show they’re like, ‘Oh, gross. That’s actually what the Weeknd is like.’ The line between the character and himself is really blurry, in the sense that the character's name is Tedros and his last name is Tesfaye. And the character is like really hypersexual and gritty and dark, which kind of is the vibe that The Weeknd had, especially in his earlier work.

A stretch: the name correlation and aesthetic parallels. Weird: projecting a fictional character’s personality onto an actual celebrity. Insightful: musician-fan parasociality can clearly affect audiences’ ability to consume star-studded TV with a detached, objective lens.

Le is also bothered by the underlying narrative arc surrounding Tedros’s alt-pop sex cult, which she considers non-redemptive and maybe kind of — my word not her’s — problematic.

I thought they were going to go deeper with the cult. Like I literally thought it was going to be like, a NXIVM type of storyline. But the cult stuff was very shallow. It was half-baked … And actually, in the end of the show, they all get rewarded by being scouted by these like, actual talent managers. So yeah, I feel like the messaging there is: ‘Join a cult. You might be a big pop star at the end of it.’

Definitely a patronizing way to talk about audiences, and maybe yourself too. Also boring! It’s ok to be anti-alt-pop sex cult in real life but pro-alt-pop sex cult on a fictional TV show. Why does The Idol need a proverbial cautionary-tale ending to deliver a critique?

When it comes to the gaze, Le contextualizes Depp’s pop star Jocelyn with allusions to previous criticism of director Sam Levinson’s Euphoria. Then she says this:

I mean, I like a lot of Jocelyn’s outfits as standalones. I think a lot of her looks were really nice … But I think it’s very telling that she only wears skimpy outfits. It kind of feels objectifying. She really doesn’t wear any kind of normal casual clothes even when most of the show takes place in her house.

Well. The show is called The Idol. Every character is a caricature. Among the cult members, each performs a specific, individualized, cliché sex symbol.

Do we think there’s an affective difference between “it kind of feels objectifying” and “it is objectifying?” I would say that Depp, and several of the other actors, are blatantly objectified — in a morally ambivalent sense, though.

Identity-wise, I hesitate to comment on the male gaze paradigm here (though being objectified by men is something I’m very familiar with). But isn’t the concept of a celebrity idol, such as a global pop star, a kind of objectification itself?

In her critique of Depp’s objectification, Le cites an early review in The Daily Beast: “‘The Idol’s’ Horrific Depiction of Rape Culture Is Shocking Because It’s So Lazy,” by noted adult man Caspar Salmon. Salmon’s take, written after the show’s premier at Cannes, when only two episodes had been released, is full of iconic lines like:

It’s one thing to watch a 50-minute glorified sexploitation video clip, but couldn’t the creators own up to their kinks, rather than write them off so lazily?

Drag them! Also:

Depp can almost never be filmed in anything other than a parodically skimpy outfit in this horribly ugly show; at one point she finally turns up in a t-shirt, which had the effect of a cold glass of water after trekking through a desert.

Weird thing to say!

He’s concerned the show “frames queasy sexual behavior as the highest of turn-ons,” resulting in “a horrible blurring of lines.” What lines are we talking about? Not very clear — presumably the lines between consent and rape, I guess. The word “queasy” stuck with me.

He’s also convinced that the show’s sexuality is precisely calibrated “for the benefit of, presumably, a straight male audience.” I don’t regularly talk with many straight men about HBO shows (or anything, really), so my sample might be skewed, but: I’m pretty sure The Idol is targeted to the girls and gays. Intent vs impact; I could be wrong.

Originally, the series was directed by Amy Seimetz, before she was mysteriously replaced last-minute by Levinson, who scrapped her vision to chase “a new creative direction.” Historically, Levinson makes sleazy television for teens and young adults, particularly young girls. He’s Gen-Z Ryan Murphy with EDM tendencies, or whatever.

Back to Salmon:

But Levinson (and you know this!) tries to have his cake and eat it, by simultaneously subverting and being the dirt that his series calls out … How else to explain the constant objectifying of Jocelyn, to an extent that is not supported by the show?

Really unsure what “supported by the show” means in this context, but I’m confident I disagree. The show is unambiguously about sexual imagery and iconography — about performing sex, both literally and artistically.

And frankly, if you’re going to criticize sexual objectification (in a show that is about sexual objectification), at least demonstrate you have the range to analyze those dynamics holistically. I have not seen ANYONE discussing Moses Sumney’s character, a Black RnB singer named Izaak, who functions exclusively as a sex object.

As a plot device, Izaak enters the story making a sexual proposition and exits giving a lap dance to a music producer. He’s shirtless or nude nearly every time he’s on-screen. Try to describe his personality, backstory, or motivations without invoking sex or sexuality. Do your best.

There’s a long history of objectifying and sexualizing Black men in the entertainment industry. It’s typically a blind spot among critics like Salmon — one which makes them much harder to take seriously.

But, to be clear, Izaak’s sexual objectification, like Jocelyn’s, was very intentional, at least in Levinson’s version (the only one we will ever have). Like, here’s what Sumney said in an interview with Variety:

I really wanted Izaak to be an emblem of male objectification in the show, and I was really explicit with Sam about that. Once we started going, I was just like, “Hey, we’ve seen a lot of Lily’s butt. Like, what if we saw a guy’s? You choose who that would be. But based on what you’ve written for Izaak, it might be him.” And Sam was very down with that. I think that my effort in the show is to, as much as I can as an actor, be like, “Yeah, objectify me, too.”

Wow, highly relevant overlooked commentary on this exact topic.

Wait. He has more thoughts:

I think there’s an opportunity for a really interesting cultural conversation — of course about media and TV, but largely about music — that I don’t think has really spring-boarded from the show, and I’m a little bit disappointed … I mean, of course, we’re having conversations about the male gaze, which is a very worthwhile topic, and one that I like to see happening. But I think there’s always going to be a question about, is depiction endorsement on screen?

… I think that as people watch “The Idol,” if they’re uncomfortable with the portrayal of Jocelyn’s sexuality, they should then watch a few music videos. I’m always, like, who are our biggest pop stars, what are they wearing, how are they dancing, how are they moving and how is their sexuality tied to their success?

First: depiction is not endorsement. The alternative is like, really bad for us girls. You do have to explain yourself sometimes though, and people will antifa to you if your explanation isn’t good enough.

Is the sexual objectification in The Idol male gazey? Well yes. It’s directed by a kinda creepy man. And Izaak’s objectification doesn’t change that; white men (gay and straight!) are often the ones sexualizing Black men in real life.

But again — this is obvious — sexual objectification is the actual thematic subject of the show.

To get freaky with it: we can think of idolization as a project and process of sexualization and objectification. Historically, it always has been. It’s one of the Ten Commandments, babe. World Class Sinnerrrrrr.

The show is still bad. I’m just more right about why it’s bad than you. It captures a specific moment with a certain audience and then forces a few timely topics down their throats: revenge porn, culty social scenes, self-marketing, tasteless fashion, bad music, bad sex. But it is, in fact, cringy about it, and doesn’t deliver any meaningful commentary on these topics beyond observing them.

Maybe it’s camp then? Vulture’s Choire Sicha thinks so, adamantly:

Basically, this show went over like a rape accusation at a music listening party. But! The Idol will probably age really well. In 25 years, they’ll be watching it the way we watched Beyond the Valley of the Dolls when I was a kid. Camp and trash require a generation of seasoning. The Idol will be read as an important historical document — a Faster, Pussycat! Kill Kill! of a later time.

Compelling explanation (or justification) for why I was obsessed with hate-watching every Sunday night, and why I just spent several hours of my life writing a reactive defense of Sam Levinson’s creative vision. 🍅, I know.

For the record, I do side with Hanna Phifer, who did her thing in Refinery29 a couple weeks ago:

Levinson’s career feels as if ChatGPT was to make a body of work that tried to draw off the strengths of generation-defining, boundary pushing filmmakers like Harmonie Korrine, The Safdies, Darren Arranosky, and Mark Romanek. Void of originality or verve, Levinson fills the vacancy one might think to occupy with creativity with empty debauchery.

… You would think if Levinson was truly as “porn-brained” as some have accused him of being, he would have made something more titillating, but ultimately, viewers are left feeling flaccid.

This whole subject was low-hanging fruit, if we’re being honest. Anyway. The Ringer scooped some alleged cut scenes from the show yesterday, if you’re into that kind of thing. I will not be reading them. Personally.