TikTok is owned by a company

The Morning is a serious contender for most popular email newsletter in America. It’s the flagship daily newsletter of New York Times. It has millions of subscribers. And it’s “anchored” by a very pleasant man named David Leonhardt.

Every morning, intrepid Times journalists paste a bunch of hyperlinks onto bullet points in an email template. Then Dave, our plucky protagonist, barfs out around 500 words of friendly, no-nonsense context for whichever story he thinks your coworkers might yap about for three minutes after lunch. Click and send, repeat tomorrow.

Yesterday, March 13, the U.S. House of Representatives decided they want to ban TikTok, but they’ll settle for annexing it from its current owners if necessary.

Luckily, we were not surprised by this decision at all. That’s because we read Dave’s insightful commentary about it in The Morning in the morning, about three hours before the vote.

Should China Own TikTok?

Awesome title. Great question. It would be very interesting if China bought TikTok from ByteDance, the company which currently owns it. Maybe Brazil should own TikTok. Or Estonia.

To understand why the House of Representatives will vote today on a bipartisan bill to force TikTok’s Chinese parent company to sell the platform, it helps to look at a few recent news stories:

Despite low unemployment and falling inflation, TikTok is full of viral videos bemoaning the U.S. economy. One popular group of posts uses the term “Silent Depression.” The posts falsely suggest that the country is in worse shape today than it was in 1930. (My colleagues Jeanna Smialek and Jim Tankersley reported on the posts late last year.)

Like Dave, I too get irrationally frustrated when TikTokkers aren’t sufficiently grateful for number go up. Personally, number go up makes me smile. Number go up makes me think happy thoughts. I would never complain about the standard of living in America on TikTok if I knew that number go up.

However, when I step back, take a deep breath, and eat a Snickers, I remember that number go up is not always good, and sometimes even bad. Particularly when we are working with objective, falsifiable metrics such as “in worse shape today than in 1930.”

In the very article which Dave references, we learn that “the cost of a typical house was 2.4 times the typical household income around 1940 … today, it’s 5.8 times.” We also learn that the Times reporters did not link to or cite any of the videos which made “false suggestions.”

After Hamas’s Oct. 7 terrorist attack, TikTok flooded users with videos expressing extreme positions from both sides of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, tilted toward the Palestinian side, a Wall Street Journal analysis found. “Many stoked fear,” The Journal reported. In November, videos praising an old Osama bin Laden letter also went viral.

Actually, the bin Laden stans went viral among media professionals on Twitter, not kids on TikTok. That was only after some very ethical journalists at The Guardian reactively unpublished bin Laden’s “Letter to America,” which made people post about it even more, obviously. And then TikTok shadowbanned the videos.

The Wall Street Journal analysis Dave mentions is titled “How TikTok Brings Home War to Your Child.” That headline quickly caught my attention because I myself have nine children who each spend 6-7 hours on TikTok every day.

Basically, the WSJ reporters created eight bot accounts to simulate a hypothetical thirteen year old who is exclusively interested in TikToks with footage of violent conflict. The bots were successful in watching lots of videos about the ongoing bombing of Gaza. A TikTok spokeswoman said the experiment “in no way reflects the behaviors or experiences of real teens on TikTok,” which is correct.

The Journal labelled 59% of videos the bots observed as “Pro-Palestinian,” 15% as “Pro-Israel,” and the remaining 26% as neutral. That’s an interesting statistic. Another interesting statistic is that at least 96% of people killed since October 7 — over 30,000 in total — were Palestinians.

In December, a Rutgers University research group concluded that videos about topics the Chinese government dislikes — including Tibet, Uyghurs, Hong Kong protests and the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown — were strangely hard to find on TikTok. All were more prominent on Instagram. “It’s not believable that this could happen organically,” a Rutgers expert told my colleague Sapna Maheshwari.

Here’s how this study went down: these guys took the raw number of search results under a bunch of normal hashtags on Instagram and TikTok and then compared the ratios. So 5.8 million #Eminem posts on Instagram divided by 3.2 million # Eminem posts on TikTok equals 1.8, or about a 2:1 ratio.

Then they did the same thing for “topics directly sensitive to the Chinese Government.” 298,000 #Uyghur posts on Instagram divided by 34,000 #Uyghur posts on TikTok equals 8.7, or about a 9:1 ratio.

This methodology is sketchy for several reasons: Instagram has been around much longer than TikTok; time was not a variable in the analysis; many people don’t use hashtags; most of the “sensitive” hashtags peaked in news relevance before TikTok was as popular in America as it is now.

Even stupider, in my opinion, is the language bias. The researchers compared English hashtags about American pop culture topics to English hashtags about foreign political topics. When non-English speakers post about #TaylorSwift, they are likely to use the English name “Taylor Swift.” When non-English speakers post about non-English geopolitical topics, they’re more likely to use their native language.

Let’s try this out ourselves, using #VivaPalestine. 10,899 #VivaPalestine posts on Instagram divided by 1,822 #VivaPalestine posts on TikTok equals 5.98, or about a 6:1 ratio. By the same logic, this would suggest that TikTok is also censoring pro-Palestine posts in Spanish — even though Dave just insinuated that TikTok pushes a pro-Palestine bias.

On Monday, the top U.S. intelligence official released a report saying that the Chinese government had used TikTok to promote its propaganda to Americans and to influence the 2022 midterm elections. This year, the report warned, China’s ruling Communist Party may try to influence the presidential election and “magnify U.S. societal divisions.”

If you Ctrl+F in the document linked above, you will find the word “TikTok” used only once, in a single bullet point: “TikTok accounts run by a PRC propaganda arm reportedly targeted candidates from both political parties during the U.S. midterm election cycle in 2022.”

Notably, the Chinese government did not “use TikTok to promote its propaganda to Americans.” It ran individual accounts on TikTok which posted videos targeting American political candidates during an election season. Would be a shame if any Americans were also posting TikTok videos targeting political candidates during an election season.

There does not seem to be any historical precedent for TikTok’s role in the United States today. The platform has become one of the country’s biggest news sources, especially for people younger than 30, and has collected vast amounts of information about Americans.

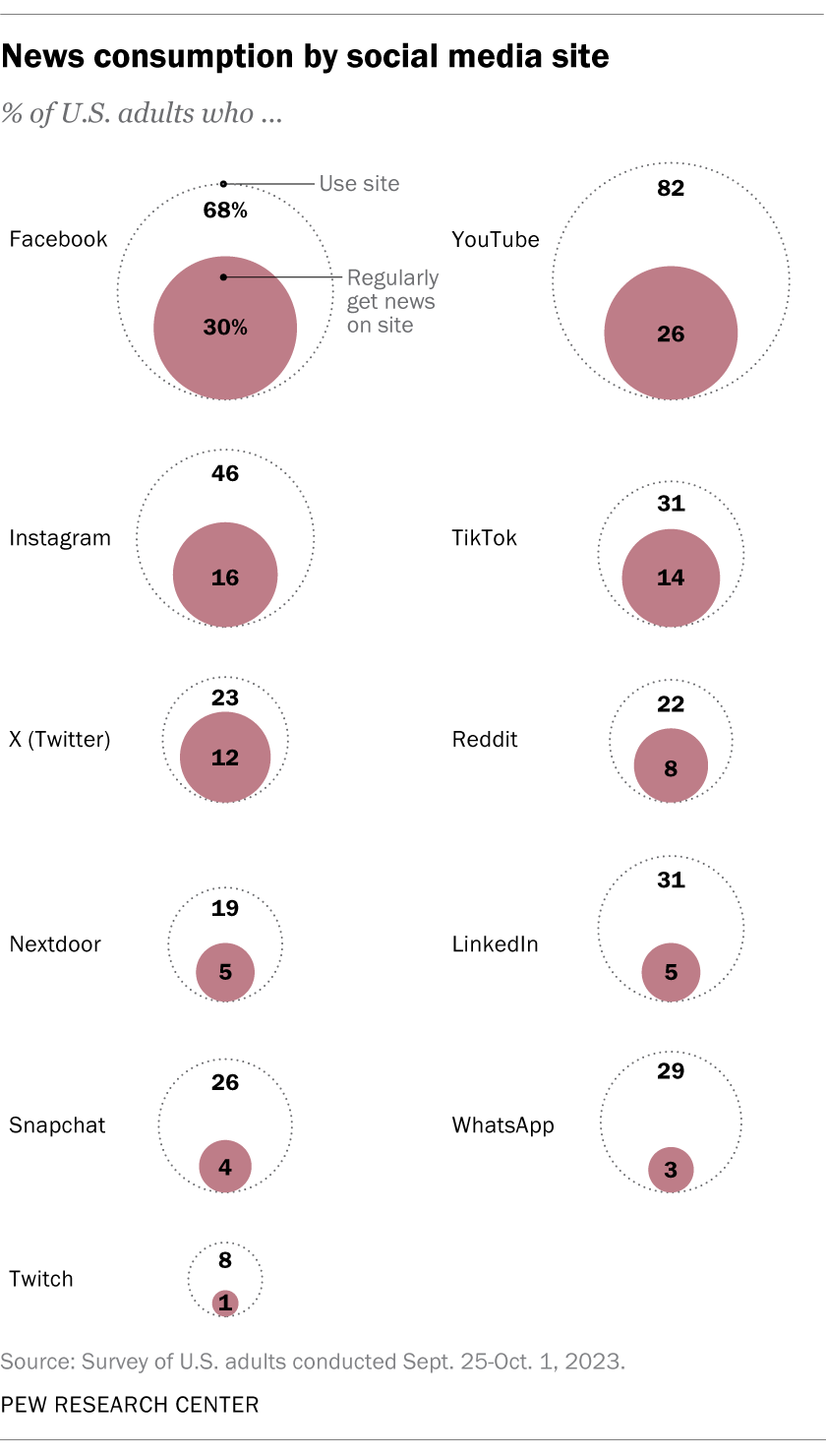

TikTok is not a news source. It is a social media platform on which some people post news. Because they are very intelligent, the researchers at Pew Research Center, who Dave cites, do not refer to TikTok as a news source. The survey data therefore does not indicate that anyone considers TikTok a news source, because that is not how surveys work. It’s just a place where people get news sometimes.

It’s not really one of the “biggest” places where people get news either. Let’s circle back to that Pew data, Dave.

In 2023, American adults were more likely to get news from a news website or by searching the internet than via social media. Even Americans ages 18-29 got news from search more often than from social media.

Only 31% of adults regularly used TikTok, and only 14% regularly got news on TikTok — more than twice as many Americans regularly got news from Facebook (30%). Plus, only 12% of Americans said social media was their preferred way to get news, which means many people are probably seeing news on TikTok unintentionally, and likely ignoring it.

TikTok is also owned by a company,

TikTok is also owned by a company.

TikTok is also owned by a company, ByteDance, that’s based in a country that is America’s biggest rival for global power: China.

To recap, the five reasons the House voted to ban/annex TikTok are:

- Young people sometimes post negative opinions about the cost of living in America on it

- Teenagers can hypothetically watch videos about the ongoing mass murder of Gazan children on it

- There’s not enough posts about Uyghurs, Tibet, and Hong Kong on it

- The Chinese government posted some videos about American politics on it

- China is bad

This goes on for a while. We’ll briefly touch on the highlights.

With any one viral video or trending hashtag on TikTok, it is impossible to know whether China’s government is playing a role. Some of the videos go viral on Instagram too, for instance. But there does seem to be a pattern. The most sensitive subjects for Beijing — such as Tibet and the Uyghurs — are hard to find on the platform. Information that is consistent with Beijing’s narratives — such as its pro-Hamas tilt and its criticism of the U.S. economy — circulates more widely than the opposite.

It’s also impossible to know whether China’s government is cheating with your wife. But there does seem to be a pattern of your wife traveling to China every weekend lately, and some weeknights too.

What Dave is saying here is that there’s not really any evidence, that we know of, for any of this. At this point, all of Dave’s claims regarding Chinese influence are unverified conjecture and untested hypotheses based largely on anecdotal data and flawed research methodologies, fueled by an instinctive distrust for any organization with vague ties to the Chinese government — in other words, conspiracy theories.

As an analogy, imagine if a U.S. company with close ties to Washington were a leading source of news in China today. Or imagine if a Soviet organization owned a U.S. television network in the 1960s — and it was a leading news source for Americans under 30.

As an analogy, imagine if a Chinese guy who worked closely with your wife was hanging out with your wife after work every night. Or imagine that a 95-year-old Russian guy owned one of the most popular spas in the neighborhood — and it was your wife’s favorite spa for some reason.

It’s not clear what will happen. But the chances of the U.S. government acting against TikTok have risen significantly in recent months.

Make up your mind: The A.C.L.U. and Tyler Cowen make the case against forcing a sale. Noah Smith and Matthew Yglesias make the case in favor.

Whose opinion do you trust more: The American Civil Liberties Union or two guys with Substacks?

Here’s some other things you could read instead, in order of most to least serious:

- Congress should give up on unconstitutional TikTok bans • Jason Kelly & Paige Collings

- The U.S. wants to ban TikTok for the sins of every social media company • Jason Koebler

- What if nobody owned our children’s data? • Ryan Broderick

I lied about the hiatus. If you subscribed to emails: I’m aware the formatting sucks. I’m working on fixing it, or finding something different. LMK if you have any input. Nice blogging with you. Happy Friday!